Richard Miller, Bohemia: The protoculture then and now

Victor Hugo's Romantic Army (1830)

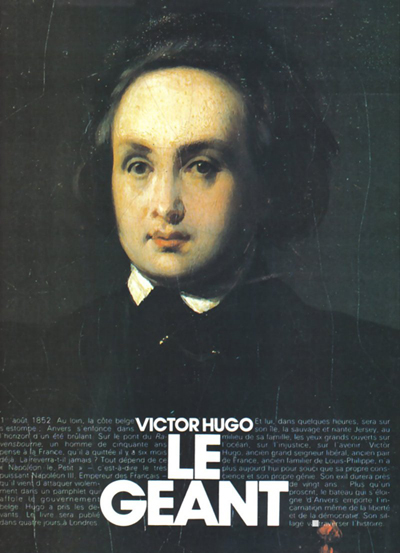

Richard Miller traces the development of counter cultures back to the premier of Victor Hugo's play Hernani in 1830. Hugo was then a young Romantic poet and playwrite, whose work had been censored by the government. A group of scruffy young would-be artists had rallied to his cause and made the opening of his play a cultural event that echoes through French culture down to the present. It provides a very early example of the way that the support of a Bohemian subculture could lend moral support and help generate publicity for works that were rejected by the conservative establishment.

Miller obviously identifies with the young supporters of Hugo and idealizes their cause. But the romanticization of this event in cultural history became a force in French culture, providing a model for artistic protest that would be repeated down to the present.

Four days later the play was accepted for production by the Theatre-Français -- the first theater of France, the Bastille of neoclassicism, and, considering that plays to people then were as television is to people now, the CBS of the nation. But then came a traumatic shock: the state censor refused to authorize the production. Hugo appealed to the king's first minister, the Vicomte de Martignac, who soon informed him that its portrayal of Louis XIII constituted a threat to the monarchy. Hugo then went to the king himself. Charles X received him graciously, promised to read the offending passages, did so, and sustained the prohibition. Because Hugo was still thought a monarchist, the government tried to soothe his feelings by offering him a substantial new lifetime pension. This he refused in a dignified letter -- the text of which reached the press, instantly generating an enormous swell of sympathy for the twenty-seven-year-old Prince of Youth. Bent on revenge, Hugo took the Spanish story he had previously rejected and, concentrating all his astonishing energy on it, he began to write a new play. That was on 29 August 1829. He finished Hernani or Castilia Honor on 25 September, read it to his friends on 30 September, presented it to the Theatre-Française on 5 October. The theater accepted it; the censor -- reluctantly -- passed it.

Four days later the play was accepted for production by the Theatre-Français -- the first theater of France, the Bastille of neoclassicism, and, considering that plays to people then were as television is to people now, the CBS of the nation. But then came a traumatic shock: the state censor refused to authorize the production. Hugo appealed to the king's first minister, the Vicomte de Martignac, who soon informed him that its portrayal of Louis XIII constituted a threat to the monarchy. Hugo then went to the king himself. Charles X received him graciously, promised to read the offending passages, did so, and sustained the prohibition. Because Hugo was still thought a monarchist, the government tried to soothe his feelings by offering him a substantial new lifetime pension. This he refused in a dignified letter -- the text of which reached the press, instantly generating an enormous swell of sympathy for the twenty-seven-year-old Prince of Youth. Bent on revenge, Hugo took the Spanish story he had previously rejected and, concentrating all his astonishing energy on it, he began to write a new play. That was on 29 August 1829. He finished Hernani or Castilia Honor on 25 September, read it to his friends on 30 September, presented it to the Theatre-Française on 5 October. The theater accepted it; the censor -- reluctantly -- passed it.

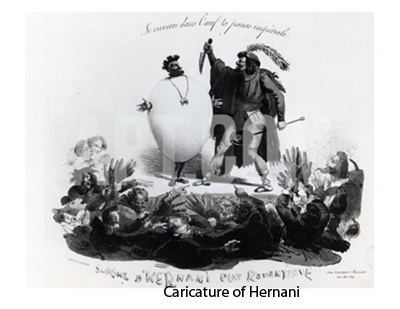

Hernani breaks most of the rules of neoclassical drama ; it rapes the three unities [rules set down for drama by Aristotle]; its down-home dialogue in the mouths of the mighty - as when the king asks "Is it midnight?"-affronted convention; its wild, passionate, uninhibited tone is anathema to the principle of neoclassical restraint. . .

In many ways, Hugo's real situation was as desperate as that of the fanciful Hernani. Some passages of the play had been smuggled out, by the cast, by the censurate, and were being mocked in music halls and critical columns. The police showed deep concern. His finances lay in ruins. Some of his old apostles turned on him. Then Nodier of the Salon de l'Arsenal castigated him in print. "Et tu, Charles!" Hugo replied in anguish. The cast, fed for so many years on neoclassics, became obstreperous. The professional claqueurs [people hired to applaud at the right places during plays] embodied a strong neoclassical bias and an insatiable greed. No longer having time to go home to Adele and the children, he had to take rooms nearby. He felt, as he confided, "crushed, overladen, choked."10

Because he had led the way in the fight to set art free without once betraying the confidence of the young believers, he still had one resource: the flaming faith of youth. Recently he had declared that in the "garden of poetry" there is no "forbidden fruit." In a published letter then being discussed, he had gone on record with "liberty in art, liberty in society," that is the dual standard which rallies "all the youth, so strong so patient.. .. Literary liberty is the daughter of political liberty. This is the principle of the century. To a new people, a new art."11

The issue was clarified; the decisive battle imminent. In cafes and dining rooms and newspapers, the dispute swelled to passionate intensity. In this relatively small city of so much spirit and, by today's standards, of so few amusements, the anticipation of Hernani aroused an absolute sensation. The students of painting and sculpture of all the studios seemed ardently determined to help this prince who fought so nobly for the freedom and glory of art. But how to use them?

As early as 1821 at the Odeon Theater, in a hurricane of shouts and whistles, a barrage of baked apples and theater seats, the students had overwhelmed plays suspected of clericalism, royalism, classicism.12

Conversely, in 1827, at the head of his apostles, Hugo had gone to applaud an English company producing the scandalous Shakespeare [Shakespeare was considered a poor writer by the classicists, but he was idealized by the Romantics]. . . .

To an astonished public, Hugo announced that for Hernani he would employ no professional claque.

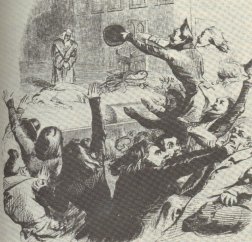

Instead, he had determined to enlist a romantic army from the Latin Quarter, using the young members of his cenacle as recruiters and staff. The Napoleon of poetry would plan a military campaign against the forces of classicism; his romantic army would occupy every strategic point in the theater and overcome the opposition. At home, Adele Hugo was soon surrounded by a fanatic elite force of young longhairs studying the map of the theater and preparing for eventualities. Day after day, some eighty hirsute volunteers passed up and clown the stairs of the house. Inside, they reported on progress, consumed free wine and food, received instructions, reveled at late parties. The landlord, an old man living downstairs, annoyed and frightened by these outrageous young zealots, eventually gave the Hugo's notice.

Instead, he had determined to enlist a romantic army from the Latin Quarter, using the young members of his cenacle as recruiters and staff. The Napoleon of poetry would plan a military campaign against the forces of classicism; his romantic army would occupy every strategic point in the theater and overcome the opposition. At home, Adele Hugo was soon surrounded by a fanatic elite force of young longhairs studying the map of the theater and preparing for eventualities. Day after day, some eighty hirsute volunteers passed up and clown the stairs of the house. Inside, they reported on progress, consumed free wine and food, received instructions, reveled at late parties. The landlord, an old man living downstairs, annoyed and frightened by these outrageous young zealots, eventually gave the Hugo's notice.

The manager of the theater had agreed to admit 1,500 of Hugo's friends free and early. To identify them, Hugo issued red cards stamped HIERRO, Spanish for iron, which reference the young artists recognized as being to a war cry from Hugo's Orientale VI, a poem they knew by heart. . . .

In the side door they came, settled into their assigned places for a four-hour  wait. Presently the first formation of the romantic army was marshaled on the field, men like Edouard Thierry and Hector Berlioz, with his mass of bronze-colored curls: in all, 500 zealous fighters for the freedom of art. The battle "would soon begin . Five months hence some would be among the 6,000 Parisians dead on the barricades of the Revolution of 1830. Anything could happen. One lad turned to the adolescent nobleman and said: "You can well believe that the success of the new play is only secondary for us. That which we want, and it's not all that difficult, is to conquer Victor Hugo for our cause.. .. He leans there; he must fall there.. , . Yesterday, he was royalist; today, he is neutral. Tomorrow he'll he a revolutionary!" Hungry, they began opening their provisions, spreading ham, butter, bread, cheese, and garlic sausage out on handkerchief and bench. Wine appeared everywhere. Sitting there in the theater of Moliere and Racine, the first theater of France, they shared everything; they laughed and sang and imitated the cries of animals and drank so much that some went into the boxes seeking out dark corners in which to piss -- this because they'd been locked in and the toilets were still closed. . . .

wait. Presently the first formation of the romantic army was marshaled on the field, men like Edouard Thierry and Hector Berlioz, with his mass of bronze-colored curls: in all, 500 zealous fighters for the freedom of art. The battle "would soon begin . Five months hence some would be among the 6,000 Parisians dead on the barricades of the Revolution of 1830. Anything could happen. One lad turned to the adolescent nobleman and said: "You can well believe that the success of the new play is only secondary for us. That which we want, and it's not all that difficult, is to conquer Victor Hugo for our cause.. .. He leans there; he must fall there.. , . Yesterday, he was royalist; today, he is neutral. Tomorrow he'll he a revolutionary!" Hungry, they began opening their provisions, spreading ham, butter, bread, cheese, and garlic sausage out on handkerchief and bench. Wine appeared everywhere. Sitting there in the theater of Moliere and Racine, the first theater of France, they shared everything; they laughed and sang and imitated the cries of animals and drank so much that some went into the boxes seeking out dark corners in which to piss -- this because they'd been locked in and the toilets were still closed. . . .

"It sufficed to glance at this public to convince oneself that this was not a matter of an ordinary representation; that two systems, two parties, two armies, or even two civilizations-and that's not saying too much-were present."20 Victor Hugo, looking out through a hole in the curtain, must have shared Gautier's impression . From top to bottom, the room was all silk, jewels, flowers, bare shoulders, wigs, bald heads -- and romantics, dressed, as Adele [Hugo]put it, in every fashion save the fashionable. Already the two sides had clashed . Unable to bear further the sight of the society types, a young sculptor screamed out: "Skinheads to the guillotine!" Honore de Balzac, Alphonse de Lamartine, and Stendhal and Chateaubriand sat out there, sympathetic but detached from the romantic escadrilles; at age thirty, thirty-nine, forty seven, sixty-one, they did not burn with the same spirit. For Hugo, the suspense was terrible. When he had arrived, the manager, horrified by complaints about silk dresses and satin shoes being fouled in the pools of piss, said, "Your play is dead" and "it was your young friends who killed it." No, said Hugo, not them, but who - ever it was who locked them in for four hours. The manager tried to keep this scandal from the leading lady, but Hugo's enemies saw to it she was informed. Furious, on first catching sight of him she said: "All right, you have some nice friends! You know what they did!" Well, "it's your romantic young friends who've ruined us."

In Adele's words, "Actors, extras, stagehands, ushers had passed from frigidity to hostility."27

The footlights are lit; the curtain draws open.

The audience sees an old woman dressed in the mode of Isabelle the Catholic moving about a dim chamber. From behind a panel, two knocks. "Can he be here already?" Another knock. "He is indeed-at the hidden stairway (escalier dérobé)."

In the audience an old gentleman snorts: "Escalier dérobé! That doesn't even scan!" Now the battle joins. The army shouts defiance. From the enemy: "Throw them out!" The audience trades insults; the tumult rises to white intensity -- subsides, the suspense of the plot, the poetry of the lines, causing everyone to hush. Then a new burst of outrage, followed again by silence. Cowed by the ferocious romantics, society, both individually and in the mass, refrains from giving full voice to its anger. . . .

Dona Sol's senile old guardian appears and holds Hernani to his promise of suicide. The lovers take poison and expire. The lights go up; the army, transported by feeling, thunders ovation. Hugo has left, but in the author's box Adele still sits. Tall, dark-eyed, a white ribbon around her head, at twenty-five she radiates an impressive beauty. The ovation turns to her; she, known to be the model of Dona Sol, receives it in cool classic dignity. The next morning, Hugo's twenty-eighth birthday, FrançoisRene de Chateaubriand, whom Restoration youth once regarded as the first poet of France, wrote him: "I am going, sir, and you are coming."3o

At the intermission that first night a publisher offered Hugo 5,000 francs for the book rights. Hugo had but fifty francs left to his name. 31 A week later, in the first entry of a new .Journal, Hugo wrote: "Hernani's been playing at the Theatre-Français since 28 February. Each time it makes 5,000 francs in receipts. Each night the public hisses all the verses; it's a real uproar, the parterre hoots, the boxes explode into laughter. The actors are mortified and hostile; most of them sneer at what they have to say. The press has been close to unanimous and every morning keeps on jeering at the play and the author. If I go into a reading room, I cannot pick up a paper without reading there: 'Absurd like Hernani; monstrous like Hernani; silly, false, turgid, pretentious, extravagant, incoherent like Hernani.' If I go to the theater during the play, at each instant, in the corridors where I hazard myself, I see spectators leaving their boxes slamming the doors in indignation.

At the intermission that first night a publisher offered Hugo 5,000 francs for the book rights. Hugo had but fifty francs left to his name. 31 A week later, in the first entry of a new .Journal, Hugo wrote: "Hernani's been playing at the Theatre-Français since 28 February. Each time it makes 5,000 francs in receipts. Each night the public hisses all the verses; it's a real uproar, the parterre hoots, the boxes explode into laughter. The actors are mortified and hostile; most of them sneer at what they have to say. The press has been close to unanimous and every morning keeps on jeering at the play and the author. If I go into a reading room, I cannot pick up a paper without reading there: 'Absurd like Hernani; monstrous like Hernani; silly, false, turgid, pretentious, extravagant, incoherent like Hernani.' If I go to the theater during the play, at each instant, in the corridors where I hazard myself, I see spectators leaving their boxes slamming the doors in indignation.

"Mlle. Mars plays her part honestly and faithfully, but laughs at it, even in front of me. Michelot plays his burden and laughs at it, behind me. There's not one stagehand, not one extra, not one lamplighter who does not give me the finger."

Why bother to hiss Hernani? Can one stop a tree from greening by crushing one of its buds?"" For forty-eight performances, ever-renewed by new blood, the romantic army kept up the fight. Inside the theater, outside in street and parlor, in the papers, the battle went on, throwing the young men of the Latin Quarter into a frenzy." In Toulouse, a young man died in a duel over Hernani. At the end, its chains broken, Romanticism stood victorious. . . .